Escape the designer ego trap

What role does your ego play in your deepest assumptions about being a designer?

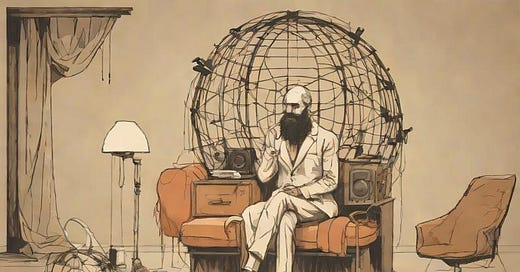

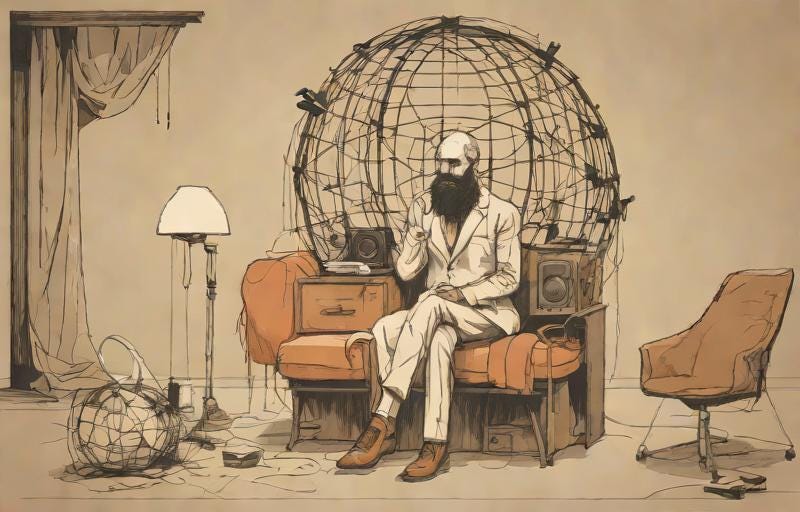

The ego trap is the belief that because you are a designer you should be the creative hero in the story of your organization. When many young designers enter the workforce they are shocked to discover they are instead treated like minor characters, and people with no design training are making most of the big design decisions. This blow is compounded by the fact that no one else in the organization seems to notice this problem and when they try to point it out, leaders get confused or defensive.

Most people suffer from a form of ego trap, at least sometimes, as we’re all the central characters in our minds. Cognitive biases like the egocentric bias and the fundamental attribution error prove we are prone to feeling special and privileged, especially in cultures that favor individualism like the U.S.. However, the role designers need to play in most workplaces, combined with our tendency to see our work not only as a job but also as our identity, makes the trap more dangerous for us.

The root of this problem is a failure of expectations. The ego trap is perpetuated in design culture, design school and design media by always making the designer the star. It’s the designer who is the main (or only) character of every design course, book, lecture, or documentary film. Designers are often portrayed as solo visionary artists rather than collaborative leaders on interdependent projects, despite how rare it is that anyone really needs to hire the former and the obvious demand for the latter.

When designers make diagrams about how design decisions or UX processes should work on a project, the designer and design work is usually in the center, to the dismay of more central project leaders, engineers, executives and sometimes even customers. Yet in the real world most people don’t know what design is or what designers do. In most organizational cultures the natural heroes are the roles who have been there longer and have historically had the most power (and they like it that way). Design often begins on the periphery of organizations, which is not a surprise to anyone except us designers.

The ego trap is popular, despite its tenuous relationship to reality, because it’s seductive and self-reinforcing. It allows a designer to believe that since it’s obvious they should be the creative hero, they can expect to walk into a project with ideal conditions already in place to allow them to focus on the fantasy of pure, frictionless creative effort. In this fantasy, there is no need to see skills like communication, negotiation, persuasion or collaboration as essential to what makes designers successful. Design schools and design books can therefore focus on the craft of working with ideas, even though we know working with ideas might be the easiest part of the job. And the ego trap fuels our blame of others when they don’t provide the environment we need (e.g. they don’t get it), even though they don’t know what it is and we haven’t persuaded them to see why it’s in their interest to provide it.

Put another way, design culture and design education is tragically self-involved. Many professional cultures have this problem, but as a professional minority, often in advisory rather than decision-making roles, this hurts us more. Lawyers and doctors can succeed in spite of their egoism because their roles are commonly understood and have been held in high regard for centuries. They can even withstand being made fun of in countless jokes, as it’s seen as punching up and not down, whereas we are in a far weaker position.

There are roughly 400k professional designers in a world of almost 5 billion adults. This means designers are .00001 of working age humanity. A good design of the design profession itself would logically train us to excel at working with people who know little about design. To be comfortable and confident in these situations since they will be the most common ones, but we do the opposite. We’ve cultivated an attitude of disappointment and frustration. We claim to be experts at psychology and empathy, yet fail to realize how our behavior is often perceived as offputting by our coworkers, as if our well-earned stereotype of black clothing, obsessions about esoteric details like kerning and furtive glances in meetings has helped us gain any influence or power.

Designers often feel ignored and undervalued but there are some clear reasons why that are under our control and we can change. We need a better way to think about what we do if we want a better designed world and that’s what we’re sharing in this book.

Does the ego trap resonate with you or remind you of designers you know? Have you been in it? How did you get out of it?

After touring colleges with my daughter - I can say for certainty this is true.

When you used the example of lawyers and doctors you made me realise something interesting. Design is fundamentally different (and difficult to compare) because what we do is "new" every time. A cardiologist, or a dermatologist, or a patent lawyer has an expertise and "customers" come to them with the problems that they'll help with. Most of the times a doctor will see 6 to 10 patients (or more) every day, helping build pattern recognition, hearing similar stories and treating similar symptoms.

In Design every project I've worked with are with different people that bring different problems and different ways of communicating it.

It's more similar to a GP rather than a doctor with an expertise. Even so, being a doctor you have a finite number of options (limited by human biology) whereas with Design it seems like we can always expand (or reduce)... we can always create something.

Yes, there are difficult designers to work with (the industry will take care of these ones). Good design is hard because of all these variables in the business and how exponentially difficult it becomes when you deal with subjective requests (most of the times). Sometimes it's easy because the briefing/problem is really good and stakeholders amazing to work with, but sometimes it takes a lot of effort to unpack what someone really wants design for.

It's as if going to a doctor very unsure of what you want out from it, or failing to communicate where it hurts... the doctor could end up sending you home to really think about where it hurts.