Scott Berkun and I are writing a book on "Why Design is Hard". To keep up with our progress, sign-up here.

I like serendipity a lot: Moments when ideas and people connect in ways that rub against the natural entropy of the universe.

My favorite form of serendipity is when I've had ideas and beliefs rattling around in my head, but lack words for them. They are patterns and hunches that strike me as true but exist beneath the surface of my conscious thinking.

The serendipity comes to life when I encounter people who hold these same hunches, but do so out loud – giving me clarity amidst the chaos we’re all surfing.

I often think of these people as friends I haven't met yet. It’s a rhythm of discovery that makes me feel less alone.

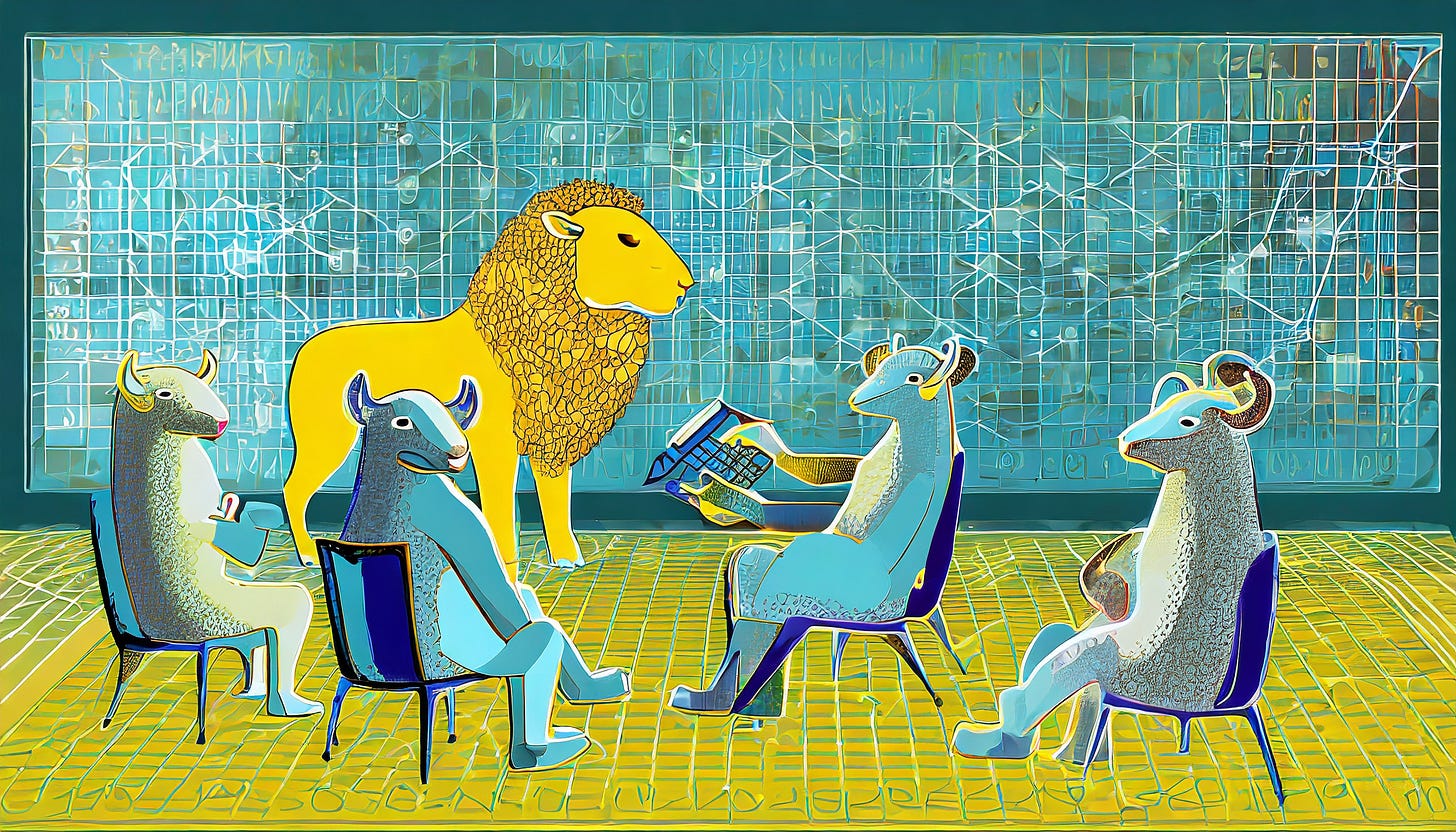

One product development provocation I've come across of late that struck me as jarringly true is this – Excel is probably your org's most common design tool.

Pavel Samsonov raised this idea in a recent thread on how design tools are mostly used to document design decisions that have already been made.

The way most designers use Figma is to produce UIs (in various degrees of fidelity) that implement decisions about the product's user experience that have already been made elsewhere. It is a documentation tool for those decisions…

…not much designing is actually going on within Figma itself because those decisions are being made outside of the tool, and typically far far upstream of it. Possibly not even by people with "Designer" in their title.

The provocative idea being that design is primarily about decision influence and decision making, and that the reality of what will and will not be made flows out of deciding and persuading activities that happen upstream of artifact generation.

In this sense, things that have historically been created in "design tools" such as Figma, Sketch, Fireworks, etc. can be seen as documentation of decisions that, for the most part, have already been made.

In my experience, the place and time where design decisions are normally made, are the common spreadsheets and briefs that drive the horse trading of annual planning season.

And if this line of reasoning holds water, we've got a lot of work ahead of us in shifting how we mentor and train people entering the product development and design field.

While documenting has its place, how we decide what problems are worth solving and what solutions are worth shipping is where the work of consequence (or inconsequence) cascades from.

In other news, if you were allergic to last year's annual planning cycle, there's a good chance you're not gonna like what you'll be Figma-ing this year.

As a product manager with a design background, this speaks to a problem I’ve come across with some designers: a belief that design happens in design tools, designers are only qualified to design, and that design must start from the experience of the consumer.

In my experience, most of the design work (what problems will be tackled, how much will be spent addressing them, how will solutions be sold/deployed) for a product happens in annual and quarterly planning and pre-planning discussions. Often those decisions are made with incomplete data and lacking the iterative refinement of most design processes. Like Figma, the Excel spreadsheet, presentation or work tracking artifacts are documentation of those decisions. From my experience, it’s the cross-disciplinary pre-planning and planning discussions where a lot of the fundamental “design work” happens that defines the constraints of the resulting design decisions.

I agree that design is primarily about decision influence and the decision-making process. Design is a team sport which extends well beyond the traditional product-engineering-design triad. When design engages in the “boring” upstream business and planning discussions, higher level decisions flow back into the detail work.