Quick note: this Substack now has 5,500+ subscribers. Thanks for being here. This week’s post is about power, a popular chapter from my primer book, How Design Makes The World.

Good design can only happen if an organization makes it possible. This sounds obvious but most of us underestimate the impact of what this means. By choosing the strategy, the budget, the culture, and who they hire, leaders have more impact on whether good work is possible than anyone. For example, CEO Alfred Sloan, who made good design the strategy for cars at General Motors in the 1930s, would never have called himself a designer. But his choices redefined how we think of a good car, as well as what the words design and designer mean today. If you have a career in UX or product management a major reason why your profession exists is Sloan and how he used his power to prove the business value of better designs.

In popular culture we’re told it’s people with great ideas that matter, but who decides what great means? Or good? The answer is it’s the people with power who get to decide. This means an organization could hire Maya Lin, Zaha Hadid, or Bjarke Ingels, three legendary skyscraper architects, but if their client ignored all of their suggestions, their skills would be rendered useless. We have the bad habit of, when seeing great works, giving the most acclaim to the designer, but as Michael Wilford wrote, “Behind every distinctive building is an equally distinctive client.” Sometimes designers are hired as design theater, so the powerful can say “we have talented designers” even if those designers ideas never go anywhere.

How power ruined the design of a city

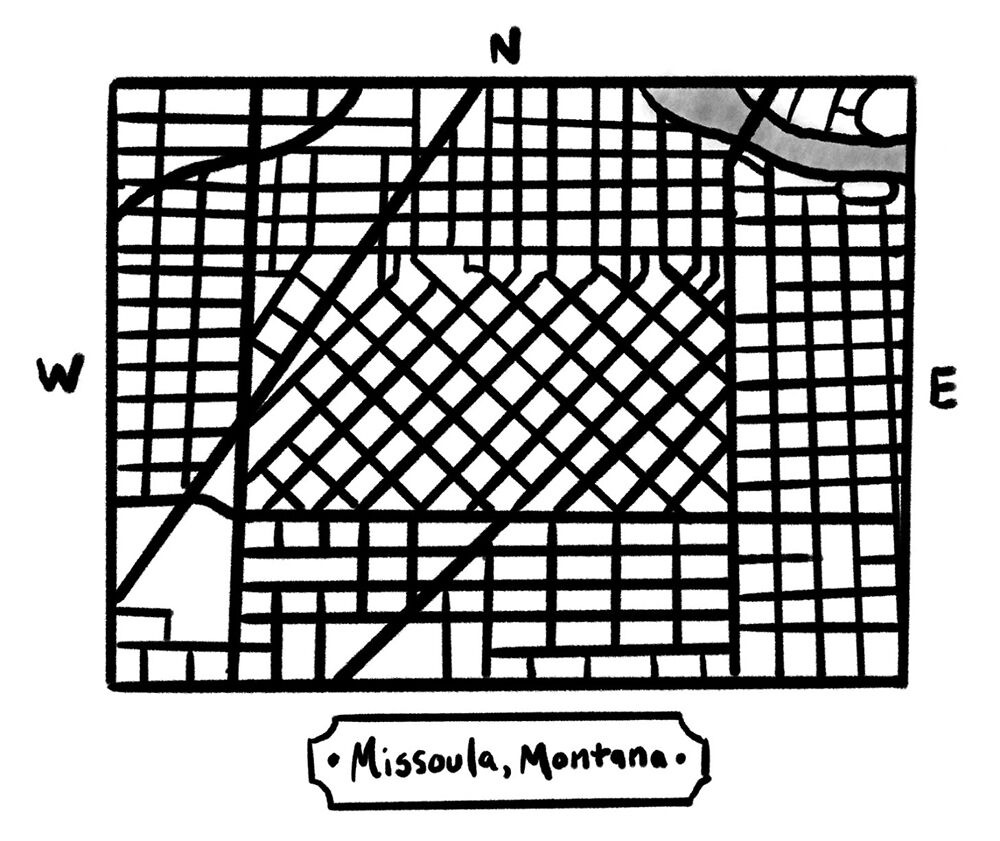

One great lesson about power comes from the town of Missoula, Montana, pictured below. Often there’s more than one person in power and their relationship defines what is possible or not, and that’s what happened here.

Missoula is a small city with one unusual characteristic: the central grid is oriented 45 degrees from the rest of the town. This makes it much harder to find your way, defeating a primary advantage of grids. What was the urban planner thinking? The answer is that there wasn’t just one plan, there were two, each led by factions that couldn’t agree. A situation that plays out in many cities, and organizations.

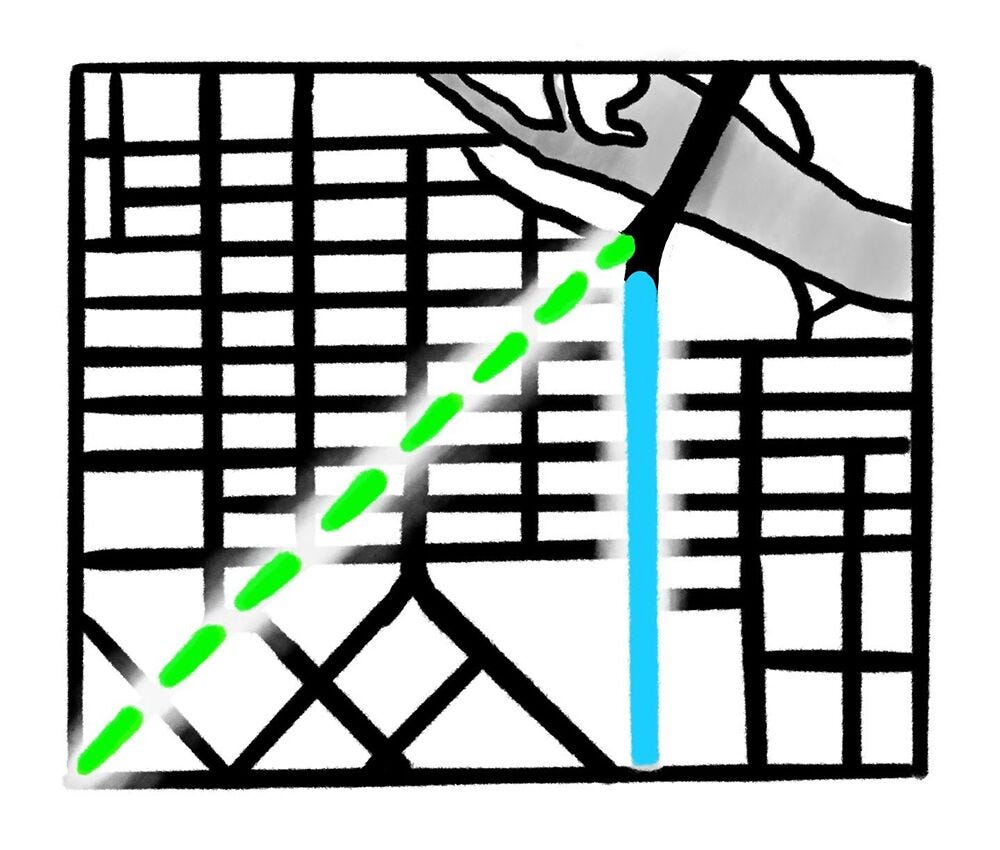

Here is how it happened. In the 1880s, two landowners, W.M. Bickford and W.J. Stephens, owned property near an old wagon road that ran diagonally through the area. They formulated their own plan to align with it, with all streets running in a grid parallel to the wagon road (which still exists today, shown with the green dashed line below). They imagined an entire town called South Missoula, with this as the core

The problem was that another landowner, Judge Knowles, owned land to the north. He didn’t like the plan that Bickford and Stephens proposed. He thought the angled roads were a mistake, since they ignored the original master section plan that much of the surrounding area was using. But he also didn’t like the idea of there being a new town called South Missoula. He was able to get the Missoula government to agree to annex his property, and installed a true rectilinear grid plan.

There was still a chance for Bickford and Stephens to have their (green diagonal) design to become the dominant one. The pivotal factor was that an old bridge on the Clark Fork River, the Higgins Bridge, needed to be replaced. Depending on how it was positioned, it would support one grid plan over the other. Whichever road the bridge fed out to would become the primary thoroughfare.

The Higgins Bridge was named after one of Missoula’s founders, C.P. Higgins, who just happened to be friends with Judge Knowles. They agreed to back the north-south (blue) alignment that Knowles had planned for, and worked together to influence citizens to take their side. Combined, they had far more influence than Bickford and Stephens, and when it came to a vote, the north-south alignment that Knowles wanted won. But the citizens of Missoula would forever pay the price.

Even today, at each intersection where the two grids meet, the single street from the north-south grid has to divide into two streets, with different names. These five-legged junctions at odd angles make it unnecessarily complicated and dangerous to find your way. The worst intersection, nicknamed Malfunction Junction, had six legs, and until its recent redesign (which took eleven years to complete) it was one of the most dangerous and frustrating intersections in America.

Power defines what is possible

This kind of design-by-politics is common, in cities, nations and sometimes even in products themselves. People in power often prioritize their own interests, which means good design to them is that which helps them protect their power. The concerns of the people who will deal with the consequences, perhaps citizens, are secondary at best.

Melvin Conway, a computer programmer, expresses this idea in a law that is named after him:

“Organizations . . . are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.”

In other words, the limitations of an organization’s politics are expressed in the design of the things they produce. When one landowner, or executive, doesn’t get along with another, the battle lines between them show up in the product itself, to the detriment of everyone.

This often surfaces in websites for large organizations, like government agencies or universities. Websites should focus on the most frequent things that people who visit need to do. Yet, leaders often assume that the view inside an organization is the best one to share with the world. But that’s like forcing someone who wants to watch a movie to think mostly about how it was made, the movie sets, the cameras, the lights and the producers, instead of experiencing the movie itself.

Good movies work because of suspension of disbelief: they are crafted to make viewers forget about what went on behind the scenes, or that there were scenes, or sets, or lights, at all. Some products suffer (like the Segway) from starting with the technology first, but more often projects are first shaped by the organizational culture. In both cases, it’s the people for whom, in theory, all of the work is being done who lose. In the end, anyone with ideas needs to see power as a necessary force to understand and influence, rather than something to try and ignore.

Get the book this chapter is from: How Design Makes The World. It teaches everyone what good design is, how it happens and what holds it back.

Conway’s Law should be taught to every entry level computer science and design student. It’s probably the most influential factor in tech companies, if not all product companies.