How to reframe your frustrations

You can reframe any problem to make it more actionable

One good definition of what designers do is repairing what is broken. Another is bringing light to darkness. A third is finding creative escapes from perceived dead ends. Regardless of how you define it, design is not a good career for people who only want to say, “this can’t be done”, or “this won’t work” or “this organization is hopeless.” Anyone can say those things—it requires no effort or creative talent. Complaining is not a skill, unless that complaint convinces someone to do something better, which complaints alone rarely do.

Most of our design hero myths exist in fantasy workplaces where the hero was never frustrated. In reality, our true heroes worked in places like all of us do, with frustrations, annoyances and challenges. Design legend Paula Scher, when trying to convince Citibank to use the logo that would eventually make her famous, she didn’t say, “To hell with these unimaginative people and their corporate bureaucracy” and quit, as fun as that might’ve been. Instead she reframed the problem and used her creative skills to try and solve it.

When Dieter Rams saw designers and engineers ignoring each other at Braun, he didn’t decide, “This brandy is too good for these Neanderthal engineers, and I don’t like schmoozing so I won’t share it with them,” even if those things were true. Instead he said “I noticed the engineers liked brandy, so I'd buy a bottle of good Cognac to share. To be a good designer, you have to be half-psychologist.”

As Anais Nïn says, “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” We interpret this to mean that when we’re ready to give up, it’s only by shifting our perspective that we’ll see the way forward.

The more direct way to make this point is: do not waste time on gravity problems. We don’t spend our time complaining about gravity, and how heavy many things are to lift, because it is an immutable law of physics. Complaining about gravity is about as useful as complaining about why time only goes forward or why dirt doesn’t taste like chocolate. In books by the Stoic philosophers like Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, they repeatedly hit readers over the head with the advice that life is better when you don’t dwell on what you can’t control—a lesson many designers desperately need to learn.

The term gravity problem comes from Bill Burnett and Dave Evans, in their book Designing Your Life. They don’t pretend that big problems don’t exist or that you should avoid them. Instead, they offer an excellent definition of what wise designers do:

The key is not to get stuck on something that you have effectively no chance of succeeding at. We are all for aggressive and world-changing goals. Please do fight City Hall. Oppose injustice. Work for women’s rights. Pursue food justice. End homelessness. Combat global warming. But do it smart. If you become open-minded enough to accept reality, you’ll be freed to reframe an actionable problem and design a way to participate in the world on things that matter to you and might even work.

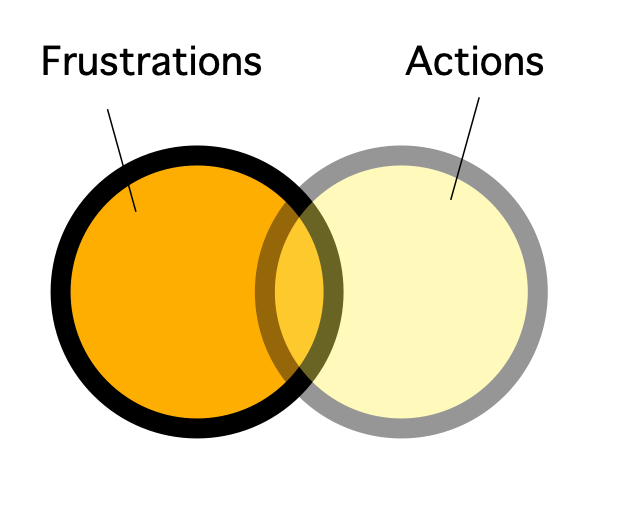

To make this clearer, we think wise designers:

Have open minds and question their own assumptions

Are rooted in the real world

Reframe (or redefine) important problems

Make problems actionable

Designers are natural reframers. That’s what we’re doing when we’re experimenting with different page layouts for a poster, or asking, “What’s the real problem we’re trying to solve?” during a chaotic brainstorming meeting. It’s just sometimes we forget how versatile our talents are: we can apply these reframing skills to the hardest problems we face. This doesn’t guarantee we will get what we want, but nothing does! What it does give us is agency and once we have that our skills work to our advantage.

Thank you for sharing the term gravity problem and its source.

Such an important topic Scott. Love this so much.