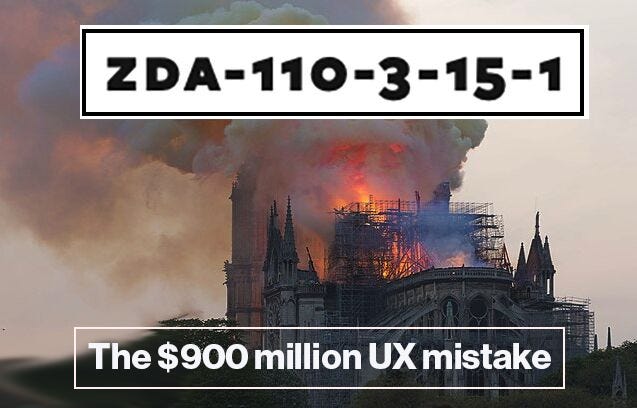

The $900 million UX mistake at the Notre Dame Cathedral fire

Will we always make the same errors in building things?

The Notre Dame cathedral reopened yesterday after $900+ million was spent restoring it from the disastrous fire in 2020. Did you know UX had a central role in what happened? It’s a good case study about Why Design Is Hard.

I reported on this story in the popular book How Design Makes The World and this is an updated version of the story for you. Please share. It’s a story every designer and engineer should know well.

At 6:18 p.m. on the night of April 15, a new security guard (it was his third day) saw a warning message on the fire safety system: ZDA-110-3-15-1. But he didn't know what it meant. It was supposed to tell him where to look for the fire but it didn’t mean anything to him and he was not trained to understand it.

To the engineers who built the system, the code identified a specific fire sensor location in the massive cathedral, but the security guard did not know this. In the confusion a second security guard looked for the fire on the wrong side of the complex. Had the fire been found early it could have been contained but the 25 extra minutes of confusion before it was found let the fire grow out of control. And it has cost almost $1 billion to rebuild.

What good is an alarm system that’s hard to understand? Not good at all. We like to think that, here in the present day, with almost nine hundred years of technological progress from the time the Notre-Dame cathedral was designed, failures like this would be impossible. The truth is that designing things well isn’t easy to do. And as a result, things that are hard to understand or that don’t work well are made all the time.

But if we have known about these design problems for so long, it’s mystifying why design related disasters like the Notre Dame cathedral fire take place.

Why does bad design still happen? (rethinking Norman doors)

Norman doors are used so often in design education that many designers find it a cliché to mention it (if this is you, a twist is coming). In short, a Norman door is one that’s designed without regard for how people naturally interact with things in the world. Here’s an example:

The problem with this door is the handle. Its shape tells your brain that you should grab and pull, like a handle on a briefcase or a car door. However, the door in this photo has a single instruction: PUSH. Which one is it then: push or pull? If we were looking at a Boeing 787 airplane cockpit or the controls for a Virginia-class nuclear submarine we would naturally feel overwhelmed, but a door is among the simplest machines in the history of civilization. We should have greater than 50/50 odds for opening it safely.

A well designed object is one we don’t have to think about. It makes the right choice the easiest one. But when we pull or push on a door and it doesn’t open we’re rightfully annoyed. Once you start looking, you’ll find confusing doors everywhere. Many modern offices have glass doors with metal handles, but the handles rarely suggest which way the doors open. A better design, one that’s foolproof because it matches how people’s brains work, is this, where the shape of the panel itself, even without text, suggests what your hand should do:

But why then are Norman doors so common? Or, more importantly, why do so many things in our daily lives have flaws built into them? There’s likely something that annoys you about your apartment or home, perhaps a window designed not to open, a room that’s always too hot or cold or a noisy pipe that wakes you in the night. Maybe you use confusing software that often crashes, or take a two-hour commute in stressful traffic each day. It could be a plastic clamshell product package that’s impossible to open or a confusing government form you have to fill out. Perhaps, in more worldly moments, you wonder why war, crime and our climate-change crisis are part of the “civilized” world, despite how few people desire them.

These things didn’t magically appear in our society one day. It’s the totality of all the choices people have made, perhaps accumulated over years or generations, that explains everything we experience, and defines who benefits and who does not. Of course, no one intends to make bad things, despite how many of them there are. Which raises the question: why are so many things in the world, like Notre-Dame’s fire alarm system or Norman doors, not designed very well?

Building vs. Designing

To understand the world, we first need to acknowledge the state of the universe: it is designed to kill us. More precisely, as best as we can tell, it doesn’t care, or even know about us. We’re lucky just to be here. In all of the indifference of infinite space, there is just one pale blue dot, where, for the moment, we have inherited a habitat in which we can survive. This improbability, combined with our uncommon talents to make tools, grow food and transfer knowledge to future generations, all without killing each other (too much), explains why we’ve lasted this long.

But this took effort to achieve. Except for nature’s gifts, we have rarely obtained good design for free. In people terms, it’s useful to think of good design as a kind of quality, and higher quality requires more skill, money or time. This means that anyone who makes something is under pressure to decide how much of their limited resources to spend on which kinds of quality. Should it be more affordable? Should it be easier to use? Should it be more attractive? It’s hard to achieve them all.

Running a business isn’t easy, and most people, most of the time, are looking for less work to do, not more. To explore these ideas, imagine there is a company called SuperAmazingDoorCo. They pride themselves on their idea of quality: making sturdy, reliable doors. Let’s pretend they manufacture the door shown earlier, the confusing one, but they don’t know it’s confusing because sales have been good and they’ve heard few complaints.

Their CEO is a proud businessperson who wants the company to be even more successful. To her, the company and its doors are designed well, since it’s making a pro!t and customers seem happy. The CEO hires you to be the project leader for a new version of their bestselling door. A team of experts at the company from across engineering, marketing and sales is brought in to work with you. In the first project meeting, some important questions come up:

From engineering: Will the new door fit in standard building doorframes?

From sales: Will it look good in the online catalog?

From marketing: Can it have optional locks? Customers want them

From the boss: Can we get this done before next year?

These questions seem fine, if shallow, at first, but something is missing. None of these questions will help the team learn about how confusing these doors are to use. This project will still build a door, but the odds are low that it will be an easy-to-use door, since no one has clearly de!ned what “a good door” means for the people who use it. Regarding ease of use , and most kinds of quality, often building things is easier than designing things.

This doesn’t mean building is easy. Building can be challenging work. Planning and installing the complex fire alarm system at Notre-Dame was very hard. But to build means the goal is to finish building. To design, or to design well, means the goal is to improve something for someone. This means that just because you built the thing the right way doesn’t mean you built the right thing. That’s the missing question from the list: How well does the current door work for the people who use it? And how can we make it better? That is, assuming we decide to care about this kind of quality. As the world demonstrates, not everyone does.

Designers do care, but they are rare. And often organizations don’t give them enough power or influence. As a result, the folks at SuperAmazingDoorCo proudly believe they make great doors, even though they don’t (at least as far as the people who try to open them are concerned). This is what psychologist Noel Burch called unconscious incompetence, where a person is unaware that they are bad at something (which may remind you of certain friends or coworkers). The way they work, not observing customers or hiring good designers, keeps them blind from the truth and unaware of their incompetence.

Much of the bad design in the world is the result of incompetence, unconscious or otherwise. As designer Douglas Martin explains, “The question about whether design is necessary or affordable is beside the point. Design is inevitable. The alternative to good design is bad design, not no design at all.”

Read the rest of How Design Makes The World - buy it on Amazon, Bookshop or anywhere books are sold. In paperback, digital and audio versions.