A personal story on designers vs deciders

A pivotal moment in my UX career and lessons learned

At the age of 22 I was the usability researcher for Internet Explorer 1.0 at Microsoft. This was in 1994: almost no one knew what the Internet or a web browser was. UX was not a term anyone used. I had just graduated from CMU with a degree in CS and philosophy so I knew what the Internet was, but no one really thought much about it then, including myself. It is a great stroke of luck in my life that I arrived at that company and on that project at that time.

But in my first year, I often gave usability advice to leaders who ignored it. They didn’t have any design training, but I did! It seemed wasteful and foolish, but I was just a kid and I felt lucky to have a job at all. But later I’d learn that most designers feel ignored a lot of the time too.

Despite my technical degree, I had trained for UI work. By my junior year I knew I was a bad programmer. I got frustrated and bored early in coding projects and was in the bottom half of talent in technical classes. In a panic-fueled skimming of the entire university course catalog, I discovered that CMU had four UX courses (called HCI or UI at the time). I took them all.

The courses spanned four departments, predating the formation of the HCI Institute: Humanities (UI Design), Cognitive Psychology (HCI Methods), Computer Science (UI Programming), and Design (senior projects course). Thanks to professors Bonnie John and Dan Boyarski for encouraging me to do it. I loved all the courses (well, I still didn’t love programming) and knew this was what I wanted to do for my career.

But in this first real job at Microsoft my skills felt wasted. I liked user research, but was told I didn’t have the visual design skills to be a “designer”, since UX design or interaction design weren’t their own job roles yet. I soon learned the designers on my team weren’t happy either: they felt their talents were wasted too.

Diagrams from real life

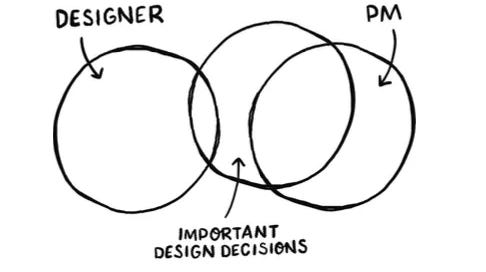

In Part 1 of the book Why Design Is Hard, there are the two diagram below. The first diagram reflects my expectations in that first job and what many designers expect too.

I expected that as the designer, or UX expert, I would heavily influence decisions. I expected this because in my college courses I made most of the design decisions on projects. All the books I read assumed it would be this way too.

But I discovered in the real world I was the only person with this expectation. Everyone else assumed the project leads, engineering leads and executives were the deciders. This is what’s shown in the second diagram.

A real life gravity story

The book explores gravity problems and how to reframe your frustrations. In Part 3 of the book, there’s this diagram.

It raises the important question: if a “non-design” job is making the decisions you want to make, why not just take that job? This is exactly what I did.

I talked to the friendlier project leads (called program managers, or PMs) about switching jobs. They coached and encouraged me (thanks Arthur Blume and Chris Brown). I interviewed with the team and got the job. I was responsible for UI and interaction design decisions, along with leading cross discipline technical teams. I was expected to make far more decisions than I bargained for, but I loved it.

I was one of the PMs on the Internet Explorer 3.0 team, and played a key role on IE 4.0 and 5.0, during the infamous browser wars. It was these experiences that led to the writing of Making Things Happen, my bestselling book on leading project teams.

The world needs good design decisions

I’m not suggesting changing jobs to get more power is for everyone. It’s really a minor point of the book. I’m aware that that even if the tradeoffs were right for you, you might not be in a place in your life where you can afford to take a risk.

So the reason I share this personal story isn’t to convince you to switch jobs (although you should consider it and the book explains why). Instead it’s to anchor the advice in the book in a real experience I had.

I want a better designed world and that comes from better design decisions. I’ve experienced most of the situations in the book myself and given advice many times to others on how to handle them, You need power or influence to make good decisions happen. There is no other way.

The diagrams in the book aren’t just speculative whiteboard scribbles. I’ve been thinking about designers and researchers and how to help them be more effective for 30 years. Even though I’ve done many different things in my life, the world needs good designers like you and I hope it helps you succeed.

Years ago I decided not to go into computer programming/writing software because I suspected I wouldn't like it. (I didn't like accounting, either) So it was so nice to read that you were like me (what I think I would be like)