One question designers hate to answer is: why are you here? Why should companies hire designers? The common answers we offer, like “we fight for the users” or “we make products better” come from design idealism rather than what executives honestly say to each other about us. We resist the painful truth that companies hire us because they expect us to generate more revenue than we cost. That’s it. Many companies don’t hire designers. Why? They don’t expect it to generate enough profit. It’s not complicated. We’re not special in this regard: all employees are evaluated in the same cold way.

Many designers are shocked to learn that:

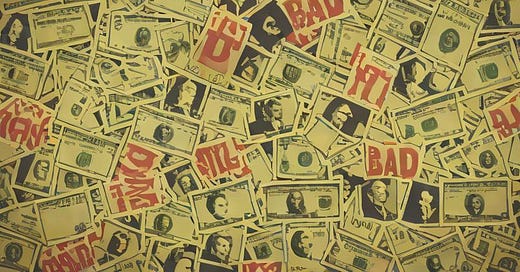

Bad design is profitable. Better design means improving quality. Quality is expensive and expenses eat into profits. Look at the market for any product, like like cars or mobile apps: what percent are designed well? 20%? 5%? Many “lesser” products we look down upon are made by profitable companies. Put simply, affordability often comes before quality in growing sales. This means many businesses can’t afford the high design quality you want to be paid well to provide. Some frustrated designers think they are Michelin star chefs but don’t realize they’re employed by the equivalent of the local fast food chain.

Business is often just math. Lets say MegaStinkCo. has 30% market share with their MegaStink7 product. They want to get to 40% but are not sure how. They could invest in design (“stinkovation!”), but leaders have little experience with that strategy. Established ones like marketing, advertising and partnerships seem wiser. It comes down to math and predictions: if leaders guess design as a strategy costs 10X to reach their goal, but marketing costs 3X, what should the CEO choose?

A monopoly with a weak product can profit more than a strong product without one. With zero competition, product quality is irrelevant: you will dominate the market (and maximize profits by not investing in raising quality). This is why many businesses seek platform dominance: it grants them effective monopolies. Tech giants like Microsoft, Oracle and Adobe invested billions to make their platforms dominant, cultivating customer dependency, so that switching to competitors with better products is prohibitive.

Of course good design is often good business, and there are exceptions to the above list, but it’s not as common as we’re led to believe.

When the goal is to gain market share, improve customer retention or develop a new product, design can be a strong strategy. However, many businesses choose other strategies like price or promotion. This means design for sale is most important. Design for sale means the priority is making choices that help sales, like adding more features, even if it makes the product harder to use. For example, microwave ovens and other appliances often have bad user experiences because having more features than competitors is a classic design for sale tactic that works: it’s only after the sale that people discover the problem. Advertising is a common design for sale strategy in commodified products like soft drinks, automobiles and fast food, where billions are spent hiring very creative people to convey an experience before the product itself is ever even purchased.

This is very different from design for use, making the best user experience. Design for use is what most designers erroneously assume is always the most important business goal. Good counterexamples include subscription businesses like your local gym or a dating app: the most profitable customers are the ones who sign up and pay, attracted by sales and advertising, but never show up to use your services. Once they’re subscribers they are all profit and no cost. And if your local gym is the only one for 50 miles, they’re also a monopoly, which means improving the gym itself might not help improve revenue.

As Erika Hall explained, we’ve cultivated the false belief that what is good for customers must always be good for business. It’s an assumption we rarely question1:

Highly-financialized businesses, platforms… and money-losing speculative nonsense alike, don't operate according to the straightforward "more user value = more business value" equation that has been treated like a law of physics in design.

In our ignorance, designers often fight for ideas unaware that they work against the business goals of our employers. And instead of investigating the business logic that explains the resistance we experience, perhaps finding the sweet spot where design for sale and design for use overlap, we resort to moral arguments (“we should do the right thing”) which we rarely win. This doesn’t mean giving up or giving in. We should of course speak up to prevent bad things from happening in the name of profit, but we need to be smart about it.

We should stay dedicated to the goal of making quality things and of making a greater society for everyone, like what W. E. Du Bois wrote:

"We should measure the prosperity of a nation not by the number of millionaires but by the absence of poverty, the prevalence of health, [and] the efficiency of public schools."

However, we need to be wise about how, when and where we pursue this. For example, if we’re hired by a megacorporation like MegaStinkCo to improve its products, we must remember this rule from designer and author Julie Zhou2:

If your company isn’t profitable after some period of time, everyone loses their jobs.

Most corporations are designed, documented in their own by-laws, to extract wealth from any source and give it to shareholders: not customers, not employers and not society. It’s foolish to pretend we work for altruistic organizations whose leaders have society’s best interests in mind. They don’t. But to Zhou’s point, if we can make arguments, perhaps against our biggest work adversaries, that are based on a “which position is most likely to help our company win?” position, rather than one about doing the right thing, the profit incentive works in our favor rather than against us, even if we’re arguing for the same idea. Schell and O’Brien, in their book Communicating the UX Vision: 13 Anti-Patterns That Block Good Ideas, add that, “to persuade people that our solution is right, we must first convince them that it isn’t contrary to their definition of right.”

Erika Hall wrote that “design is only as humane as the business model allows and rewards.” But there is more to the story. We once had healthier checks and balances between business and society, but the U.S. government’s ability to do this has been stripped away since the 1970s through deregulation and other policies. The European Union better protects their citizens from greed, which is why food in Europe is healthier and tastes better, and the biggest anti-trust threats to billionaires and megacorporations comes from the EU and not America. Society is still in charge of what business models are allowed, there was a time when slavery and child labor were legal in most countries, we’re just not as good at managing this as we need to be.

What might redeem us is to remember that design, as a skill, predates capitalism by millennia. Our ability to make tools and solve problems collaboratively is central to why our species has survived for the last 300,000 years. As a designer you and your abilities are the embodiment of what makes us special. If you have the choice, you should work for people who share higher values than profit above all. If you can use your talents in service to future generations, rather than just who pays the most, you can help save us all.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/erikahall_once-again-i-am-seeing-people-blame-designers-activity-7156370314241736704-XuKx/

A lot of this resonates with me and my experience.

One observation is that the tension between design for sale and design for use is particularly strong in organizations that are very focused on the numbers for the quarter and not thinking very much about the long term. I get that needs of both need to be balanced, but long term use is going to matter.

I also think that this might exaggerate the degree to which the cost of design for use is the reason why so many things are poorly designed... I think designers often lack the ability to make strong arguments for an improved experience of use and this accounts for at least some of the "bad design" out there. So often the rationale is "because I am a designer and I think this would be better" and that isn't very convincing.

Thanks, I'm enjoying your substack and I will check out the book!

Monopolies are indeed hard to fight against or choose an alternative.

But when there are alternatives, people can make a difference by choose what's better. However, many times what's better, easier, sustainable, etc costs more so one ends up choosing the monopoly...

Most consumers want to pay as little as possible which leads to the preference for low-quality products (explained by Gloria Origgi as 'kakonomics').