Since this book released I’ve been active on LinkedIn. I post daily and hope you’ll follow along. Like most social media, people there are rewarded for getting attention more than for clear thinking. But what happens if we slow down and read carefully? Lets find out. I came across a post that highlighted themes related to Why Design Is Hard and I’ll explore them here.

The post in question is by Jeff Mahacek, an experienced design executive, writing about why he is starting his own company. I admire him for being a founder. More designers should become entrepreneurs. It takes courage to start your own thing and by being self-employed no one can get in your way.

Where my critique begins is that his post centers on the ego trap. He holds people accountable for how things are, except for designers themselves.

ROI arguments and confirmation bias

Mahacek wrote:

A few days ago a colleague was lamenting the state of design and its place in companies… Here’s what I said to them, but I want to shout it loud for the people in the back of the room.

Every study that’s ever been done on the ROI of investing in design says the same thing - it’s a primary differentiator between the best and the rest.

I’ve read several studies on the ROI of design and I know they say different things. But the bigger problem with his claim is that being the best product is often not the strategy your organization has. Many companies have strategies based on partnerships, promotion or pricing. Those are literally 3 of the 4 Ps they teach in MBA programs (product being the forth). In blunt terms, a company can succeed against a better product by selling it for less than the competition.

While it’s fine to disagree with MBA thinking, to omit referencing it, even if just to argue against it, reflects the ego trap. Instead of articulating a coherent argument from the other side, it assumes they are fools.

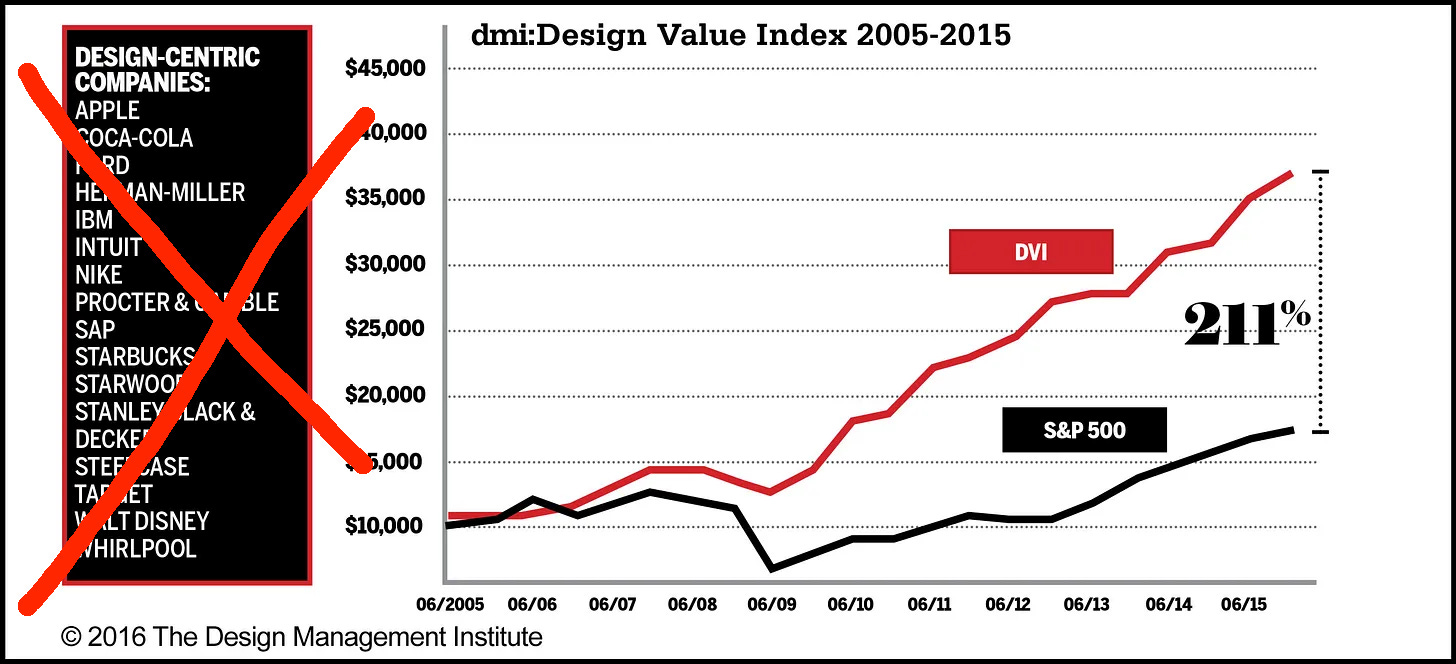

Even if we are right about the high value of design, there are always lazy arguments for our position. It’s a mistake to use them. Mahacek doesn’t reference any specific ROI study (referencing on social media is rare but should be rewarded), but this allows me to use my favorite bad example of design ROI. It’s the Design Value Index from the Design Management Institute (DMI). It has many flaws, but still gets used. It’s easily dismissed by anyone with basic knowledge of misleading charts or statistics.

Here is a rundown of its flaws:

DMI is heavily biased towards design. They are far from an independent research organization. It’s like Pizza Hut doing a study on how great Pizza Hut pizza is for you. Surprise! They say it’s really great and that you should eat it all day long.

They confuse correlation and causation. The companies they highlight have been successful for many reasons that have nothing to do with design. To claim design as the only variable is misleading.

The examples are self-serving. To call companies like Coca-Cola and IBM design centric is a stretch. Why include them? It reduces the credibility of what they were trying to do.

There are better studies to reference about design ROI. If there is interest I’ll write a future post about them. If you have a favorite, leave a comment please.

Executives invest by comparison

Perhaps a bigger lesson to pull from all this is that CEOs compare the ROI of designers against other investments. This means it doesn’t matter if designers are proven to have an ROI of 10% after expenses if there is an alternative, and cheaper, strategy that adds 20%. Any business leader compares strategies. This means design proving ROI in the abstract is not sufficient. It has to be better than the alternative investments for the specific business you are in. You have to make a local argument, not a generic one.

This is basic business logic. We follow it in our daily lives. We often buy things that are cheap or convenient. As Bob Baxley has said, even designers buy cheap and poorly designed things frequently. We rarely buy the best products because often we have other priorities. We can’t fault executives for following basic logic as they understand it.

In Why Design Is Hard, I wrote:

Business is often just math. Let’s say MegaStinkCo has 30% market share with its MegaStink7 product. Its leaders want to get to 40% but aren’t sure how. They could invest in design (“stinkovation!”), but leaders have little experience with that strategy… if leaders guess that design as a strategy costs 10X to reach their goal, but marketing costs 3X, which should they choose?

In this example we could argue that better CEOs should learn more about design as a strategy. Perhaps it’s less risky than they assume (maybe it’s only 4.5X). I’d support that. But who is capable of teaching them? It’s design leaders! If we don’t show the way, who will?

People do not magically learn things they do not know simply because we want them to. We can’t blame people for what they don’t know if we are the only people with the knowledge they need.

Mahacek then goes on to criticize an entire generation of CEOs and… people who used crayons:

The issue is a generation of CEOs who were raised on cheap capital and blue oceans who didn’t know how to weather the storm of a shift from revenue to profitability and from blue oceans to red seas. We’re seeing a lot of them make short-sighted mistakes and the design industry is paying the price because we are “a cost center” and everyone played with crayons as a child so they think what we do is simple.

I realize Mahacek is frustrated. I too have complaints about executives and late-stage capitalism. They are documented in Why Design Is Hard and and elsewhere.

But it’s worth noting this is not an argument for why CEOs should behave differently. It’s a complaint, not a solution.

To solve this we have to first recognize that many CEOs are pressured into short term thinking by their board of directors and their compensation model. More generally, it’s human nature to be short-term oriented. We’re all bad at long term thinking, as our waistlines and retirement accounts often attest. It’s also notable that the entire tech-sector has paid a price, more engineers have likely lost jobs recently than designers, but that doesn’t earn a mention. Mahacek’s focus is on a design-centric view of the world, even though the world is not design centered.

In closing he offers this:

I’m tired of justifying my team’s existence in a way no other executive has to. I’m tired of being the Cassandra of Greek myth who is cursed to see the future but never be believed. I’m tired of touching everything but owning nothing. My company will value design not because I am a designer but because I want to succeed.

I can understand why he’s tired and motivated to start his own thing. And I wish him well. Being an executive is stressful and design has challenges other roles don’t have.

Yet referring to himself as Cassandra is the ego-trap personified. It is claiming to be able to see the future (!). It is also an admission of helplessness, as Apollo cursed her to be ignored no matter what she did. This is not the situation designer usually face.

Often designers are ignored for understandable reasons. Sometimes we deserve part of the blame for our frustrations. If we are constantly disappointed it is up to us to set more realistic expectations. No one forced us to choose this career and these complaints about being ignored and disappointed have been around forever. It is par for the course for having a career where we get to work with ideas all day long. Screenwriters, musicians and artists have similiar complaints, with less pay and job security.

The way forward is to remember we have rare superpowers for working with ideas. We always have agency if the challenge is to study a problem and come up with ways to solve it. And our frustrations are a kind of problem, aren’t they?

For this reason, Odysseus is a better mythical figure for us. He was also cursed by a god (Poseidon), to spend a decade at sea before he could return home. He had to overcome unfair odds at every turn, facing shipwrecks, monsters, betrayals and the mercurial whims of Zeus and other gods. But he met these situation with intelligence, bravery, resourcefulness and loyalty. He didn’t complain much about the unfairness of the fates. Instead he reframed his situation to make it actionable, a core message of Why Design Is Hard.

My Cassandra is that things will get worse. My grievance is all sorts of crazy-Designed things, best called RI: Reverse Improvement. I just finished watching a Bill Maher video clip about RI which has regular Americans agreeing. Here's the URL

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DifysK46DO4

The Cassandra complex and grievance-mongering are two of the facets of the "gurometer" – a rather tongue-in-cheek but not-wrong method for assessing secular gurus.

Thought you might enjoy the full thing – see how many of the categories lots of designers ring the bell on.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/19PKXFn3qrzWr6nx622g9cEzyNBow0svQs_dN4fP3hjY/edit?tab=t.0

In better (?) news I've been having more conversations recently with designers who have absolutely grokked that maximising design quality and putting design in charge is a workable strategy for only a handful of companies.